The quiet architect of Bellingham hockey

Decades after breaking racial barriers in the sport, John Utendale’s influence continues to guide Western Washington’s hockey identity and inspire new generations

Story by Chayton Engelson

Published Feb. 12, 2026

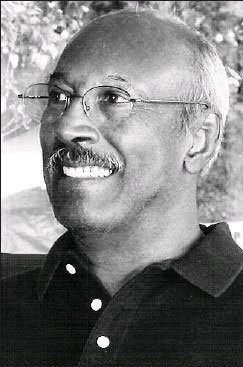

Photo courtesy of Robb Utendale.

John Utendale never played in a game for Western Washington University, yet his story lingers in the city’s rinks and the campus he once called home. Long before Bellingham had a hockey identity, he made space for himself in a sport that didn’t make room for him.

Utendale’s legacy has made a lasting impact on Bellingham’s hockey culture. In 1955, Utendale signed a contract with the Detroit Red Wings, becoming the first Black man to sign a contract with the NHL. However, he was never able to make it out of the minor league system due to racial barriers and inequities.

Utendale paved the way for future hockey players of color. Three years after he signed his contract, Willie O’Ree made history as the first NHL player of color for the Boston Bruins.

Hockey's early professional and semi-professional leagues existed in a time when segregation was common across the United States, and while the NHL never had an official ban, many teams operated in a way that intentionally excluded Black players.

Much like other sports, hockey had leagues specifically for people of color to play in, like the Coloured Hockey League of the Maritimes. These leagues produced NHL-caliber players but never received the same mainstream representation as the white professional leagues.

Utendale was no exception to the standards of the time. Jack Adams, the manager and president of the team at the time, didn’t approve of the interracial relationship Utendale had with his then-girlfriend.

“The issue was the multiracial thing,” said Robb Utendale, John’s son. “That was the issue for the manager of the Detroit Red Wings. It was not that he was Black, of course, because they had already signed him. But he had this white girlfriend, and that was not going to fly in his mind.”

Robb recalled another instance of this happening in a story his parents told him about being turned down for a house for the very same reason. These stories stand out in particular to Robb because his parents did not often talk about the challenges his father faced as a younger man trying to make it in a sport he was not welcome in.

“He was able to move on,” Robb said. “He had a lot of other skills. So it wasn't sort of ‘it's hockey or nothing.’ He was smart, very well educated.”

Utendale’s decision to continue his relationship with his girlfriend and future wife, prioritizing his family over hockey and sticking to who he is, shows perseverance through adversity. Utendale wasn’t going to change for anybody

After deciding hockey offered a limited pathway to success for someone of color, he pivoted to an area where he could make a broader impact on future generations: education. Utendale went on to earn his teaching degree and his doctorate.

Utendale didn’t just break down barriers in hockey; he also broke down barriers at Western, becoming the first Black faculty member of the Woodring College of Education in 1972. During his time at Western, he was also the faculty athletics representative from 1985 to 1996. Robb recalls the close bonds John fostered with many of his students.

Photo courtesy of Robb Utendale.

“He was really involved with his students,” Robb said. “I remember growing up that frequently we would have a lot of his students at our house, and they would have dinners or parties or barbecues. That was part of his teaching style: to be out of the classroom and to work with people in the real world, at home.”

John was also a valuable member of the faculty in his role as the faculty athletics representative and was considered a wonderful person by his colleagues here at Western, according to Paul Madison, the current athletics historian.

Still, John’s first love was hockey. The plan for his family was always to move back to Canada after five years. That was the plan when John was working for Washington State University, and the same when he was offered the job at Western. But after spending some time in Bellingham, it became clear they weren’t leaving anytime soon.

Before John moved to Bellingham, there wasn’t much of a local hockey culture. So he decided to bring hockey with him. “He teamed up with these Finnish people who were living in Bellingham at the time, and they built the arena, started the minor hockey program, and started the Western team.”

Photo courtesy of Robb Utendale.

John was one of the three founders of the Bellingham Area Minor Hockey Association and the city’s junior A team, the Bellingham Blazers. He even helped get a rink built when starting the association. John’s love for hockey was resilient. Despite the deeply rooted racism in the hockey industry, John still cared for the sport and wanted to share that with others.

Robb recalled the time he was playing on an all-gay hockey team and his father agreed to coach them. “I was 35 this time, it was an adult team, so he came up and was coaching our gay team at UBC, where he used to teach and play,” Robb said. “It was just like, wow. This was a pretty full-circle fantastic moment.”

His impact on the gay community in the area didn’t stop there. John started a gay alliance group in the late 1970s at Western.

Robb remembers his dad as a good coach and strong leader — always a competitor but urged everyone to succeed, giving all players on his teams the opportunity to play — something he wasn’t granted.

“He was really keen to see people succeed,” Robb said. “Everybody on the team played, whether it was going to help or not. I think that encompasses a certain leadership style, just like everyone gets a lift, everyone gets a chance.”

Robb still feels his father’s legacy in the community through the various ways that Utendale was recognized by the state and the impact that he had on the students he taught.

“You hear from these students or administrators in some far-flung university or something, and there was this impact,” Robb said. “When I come across them or meet them, they've been really clear about how impactful my dad's influence was on their career trajectory.”

Education was the top priority for his family and reflected how he wanted to be seen as a person. The boundaries he broke through, not only in the hockey space but also in the educational space, are lessons coaches and professors can use to continue a legacy of creating a welcoming and inclusive community.

Adam Segaar, the current head coach of the Western men’s hockey team, takes a huge example from Utendale’s story for how he coaches his team. Segaar seeks to make John proud and to continue his own coaching legacy in a way John would’ve admired.

“John never gave up on his morals, never gave up on who he was, and that is something I really look at, because ultimately, that was the reason he didn't play in the NHL,” Segaar said. "As a coach, I am who I am. I will not change who I am. I will not change my players to be anything else.”

Inclusion plays a huge part in the current team and how it operates. Segaar wants the players to feel included and the group to feel like a tight-knit family. He emphasizes that anyone can try out for the team, regardless of how much experience they have on the ice.

“Come as you are,” Segaar said. “We want you here. We want you to have fun.”