An Immigrant’s Path Toward Freedom

She left everything behind for the American dream, but never imagined how much the journey would cost

Story by Valeria Molina

Photos courtesy of Rocio Molina

Rocio Molina walks through downtown Seattle at an immigration rally shortly after arriving in the U.S. in 2002

“For the past 23 years, I have been a prisoner of my own making,” said Rocio Molina, my mother. “At 26, I made a difficult decision to leave for America and said goodbye to my family, home and culture, all for the promise of a better future. I didn’t know at the time it would be decades before I could return.”

Both of my parents arrived in the U.S. in 2002, with a tourist visa, very little money and spoke no English. Luckily, one of my mother’s sisters had made the journey to the U.S. a few years back and settled in California. They were able to join her there.

“When we first got to California, we didn’t know what to expect,” Molina said. “The initial plan was to stay a couple months to work and save up money before returning home, but finding work opportunities was not as easy as people had made it out to be.”

While her visa allowed her to be in the country, it didn’t give her the freedom to work legally. Without a proper work permit, her accounting degree was worthless.

“In Mexico, I worked so hard to continue my education. My mother and sister also sacrificed so much to pay for my school. So when I got here and realized it was all for nothing, I was at a loss,” Molina said.

Not being able to work in her field was the first freedom my mother lost. After a couple of months living in California with no prospect of employment, my parents knew something had to change. While deliberating their next step, my parents received some unexpected news: my mother was pregnant with me.

“As soon as I found out I was pregnant, there was no doubt we would be staying,” Molina said. “We both wanted to give our children as many opportunities as possible, something better than what we had.”

Now facing the reality of having a child in a foreign country, my parents realized that California was not working out as they had hoped. A call from a distant cousin came at just the right time. There was a job available for my father in Washington if they were willing to relocate.

“We realized this was our chance to make a life and a home in a place that was still so foreign to us,” Molina said. “So we packed what little belongings we had and headed to Bainbridge Island, Washington.”

When they arrived on Bainbridge Island, my father was able to start working at his family's restaurant. However, one income was not enough, so my pregnant mother found a job as a housekeeper. After I was born and old enough to attend daycare, my mother found a job at a local restaurant as a prep cook, where she has worked for the past 21 years.

In 2002, while pregnant with her first child, Rocio Molina visited Mount Rainier for the first time after immigrating to Washington.

As the years went by, my mother’s frustration with her legal situation made her seek out immigration lawyers. They all told her the same thing: the easiest path toward a green card was to wait until I turned 21 and could file a petition for her.

“I knew it wasn’t going to be an easy process, but I never expected it would take so much time,” Molina said. “I couldn’t imagine not seeing my family for that long, but I knew I had other priorities now.”

Her path toward a green card had seemed straightforward, but policy shifts and new presidential administrations made the situation even more complicated. Each year, she would diligently file taxes and important paperwork, so when the time finally came, she would be ready to present her case.

“The waiting was the hardest part. I knew until I had my green card in my hand, I would constantly be on alert,” Molina said. “I had so much anxiety. It felt like I was holding my breath for 23 years.”

A couple of months before my 21st birthday, my mother received a call from Mexico. Her mother had died. She now had to face an incredibly difficult situation; if she left to attend the funeral, she wouldn’t be allowed back into the U.S., but if she stayed, she would never get to say goodbye to her mother.

“The pain I felt when I realized I wouldn’t be able to say goodbye was indescribable. I felt trapped, and I blamed myself for being in this situation,” Molina said. “But at the end of the day, I knew there was no way I could leave and throw away the time I had already given up.”

A month after her mother’s funeral, her father died as well. Once again, she faced a heartbreaking decision.

“Having to weigh my options for the second time was even more difficult,” Molina said, “Not being able to say goodbye to both of my parents was never something that crossed my mind when I made the decision to immigrate 23 years ago.”

In the end, she made the same decision as before and lost the chance of attending her father's funeral. “I think what hurt the most was knowing how much time I had lost,” Molina said. “I paid a big price for the choices I made.”

Rocio Molina at her college graduation party, dancing with her father Emigdio Molina in 1999.

After an intense period of heartbreak, the day we had been counting down to finally arrived. The day I turned 21, I signed the application for my mother's green card, and the long process began. The immigration lawyer told us the process would take six months. However, due to the current political climate, it ended up taking much longer. A year and a half later, a letter arrived, and this time it wasn’t another request for more documents or a notice of another delay: Her application was accepted.

“I couldn’t believe what I was reading,” Molina said. “I remember my hands were shaking while I was holding the letter. I had to re-read it over and over until it set in. I was finally free.”

The next couple of weeks were a blur of signing documents and appointments. She received a new passport and a Social Security Number. As excited as she was for this new period of her life, she couldn’t help but feel anger and resentment for how complicated the process had been.

“People sometimes think that the process is very simple. It's not,” Molina said. “Small things like applying for Medicare or food stamps can negatively affect your chances of getting approved. It’s like they’re making it difficult on purpose. The system is working against us. Most of us also pay taxes, which helps fund those federal programs, but we can’t receive any benefits because we don’t qualify due to legal status.”

“It’s a bittersweet moment,” Molina said. “On one hand, I am so grateful and excited for what is changing in my life. I may even go back to school. But I can’t help thinking about how long I waited for this moment, and how difficult it was.”

Over Memorial Day weekend 2025, my sister and I had the opportunity to take my mother out of the country for the first time in 23 years. As we approached immigration services, we looked at one another with tears in our eyes because we knew how much this moment meant. My mother, who always dreamed of traveling, was finally going to see the world.

“There’s so many things I want to learn and see,” Molina said. “My plan is to return home to Mexico for Christmas this year and, in the meantime, take some classes at the local college. In August, I will be celebrating in Italy and France, something I didn’t think would ever happen. I’m finally going to be able to start living my life to the fullest.”

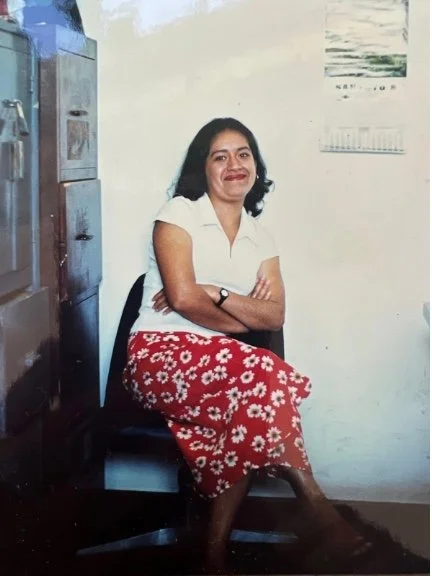

Rocio Molina, sitting cross-armed and smiling in Mexico during her accounting internship in 1998