When Bellingham Ran on Rails

How the trolley system shaped Bellingham

Written by Tyler Noonan

Photos courtesy of The Whatcom Museum Photo Archives

Illustrations by Grace Matson

Many residents of Bellingham, Washington have heard whispers of the city’s old trolley system. Few know these streetcars weren’t just a way people got around, but a result of a rivalry between two towns: New Whatcom and Fairhaven, shaping the way Bellingham exists today.

For some, like Bellingham local historian Jeff Jewell, streetcars evoke a sense of nostalgia and romance, a feeling of the past that brings excitement.

Bellingham Bay Electric Street Railway entered the streetcar scene on March 28, 1891, according to Daniel E. Turbeville III’s The Electric Railway Era in Northwest Washington, 1890-1930. They built in New Whatcom but were denied access to Fairhaven.

Instead, Fairhaven supported a homegrown company. Fairhaven Street Railway began running trolleys on Oct. 19, 1891. Eager riders piled on so tightly that it took three attempts to climb the Harris Street hill.

Lake Whatcom Electric Railway was established in June 1891, aiming to sidestep Bellingham Bay Electric Street Railway by merging their New Whatcom tracks with Fairhaven Street Railway first. Fairhaven was still unwilling to connect, resulting in a stalemate.

Jewell explained the inconvenience this dispute had on New Whatcom and Fairhaven residents.

“People going between the two [trolley lines] had to go up [State Street] hill, which wasn’t paved, and you had to pay a fare at both ends,” Jewell explained. “The streets were muddy.”

The public hated this system, Jewell elaborated. There was an outcry for the lines to be connected, and the public won after about a year.

On Feb. 3, 1892, the unfinished Lake Whatcom Electric Railway and Fairhaven Street Railway agreed to reorganize into one company. Still, the towns debated which should come first in the new name, “New Whatcom” or “Fairhaven.” To settle, a coin was flipped, resulting in the formation of the Fairhaven and New Whatcom Railway, Jewell said.

On Feb. 18, 1892, the grand opening was held. New Whatcom and Fairhaven city officials rode the trolley together to Lake Whatcom to celebrate.

Bellingham Bay Electric Street Railway sold control of their company in June 1892, leasing their assets to Fairhaven and New Whatcom Railway for $1 a month until dissolving in November 1907.

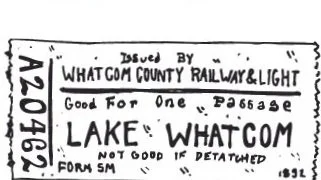

This consolidation extended beyond tracks, as on Oct. 27, 1903, the two cities became one: Bellingham. This union is credited to the trolley system physically connecting the towns, Jewell explained. Around this time, the railway changed its name to Whatcom County Railway and Light.

With the new name came new responsibility. Whatcom County Railway and Light was required to grade, pave and maintain the public roads they utilized, creating the roads we drive on today.

Robert Clark, a railroading enthusiast, noted the influence of trolleys.

“Bellingham, like most cities, was in large part built on the back of the trolley,” Clark said. “The trolley lines dictated where the city grew.”

In 1912, a half-mile extension to connect the Fountain district to Cornwall Park for residential building was added. With this extension, the trolley system reached 13.88 miles of track — its all-time peak.

Automobile competition began in 1915 with the jitney, a ridesharing service. Additionally, World War I resulted in a labor shortage, slowing streetcar maintenance. These challenges left the streetcars struggling to survive.

The introduction of the Birney car in 1917 helped them bounce back, as it could be operated by one person rather than two. This saved money on wages and boosted efficiency, keeping them afloat.

The trolley’s decline sped up in 1922 as the personal automobile skyrocketed. Highway construction began in Northwest Washington as part of a tourism push and buses were introduced, making the comparatively inefficient trolleys obsolete.

Trolleys’ and automobiles’ incompatibility played a role in the trolley’s decline. They frequently collided, which was a legal and financial issue for the trolley company.

“All through the 30s, there’s a battle in the streets, right, it’s like kamikaze autos hit trolleys, trolleys hit cars,” Jewell said.

By 1925, automobiles overtook trolleys as the way to get around Bellingham, pushing residential areas beyond their tracks’ reach. For years, they clung to life, but on New Year’s Eve, 1938, the final streetcar ran, marking the end of Bellingham’s streetcar era.

Although trolleys are long gone, their impact on the growth and structure of Bellingham persists. Downtown areas formed as shops surrounded popular trolley lines. Commercial districts like the Fountain District and Silver Beach formed because of trolley expansion and still remain today.

The same goes for Bellingham’s neighborhoods. Homes clustered along streetcar routes, creating what are now called streetcar suburbs, Jewell explained. Neighborhoods like Happy Valley, York, Roosevelt and Sunnyland exist because of trolley expansion.

Today, some believe that the trolley should come back, including Clark.

“I would love to see it happen,” Clark said. “It’s not impossible, it takes sort of a civic will and desire.”

Jewell, however, is less enthusiastic.

“As much as I love them and wish they were never taken away, I think that battle was fought and lost years ago,” Jewell said.