The Life and Times of the Outback Farm

The Outback Farm’s origins in collective ownership could return with new Fairhaven College Learning Community program

By Zoe Deal

The grooves in Weston Shroud’s worn hands are lined with dirt — so are his clothes, sandaled feet and sandy-blonde hair.

He works quietly and leads by example.

On a Wednesday in late April, a dozen work party volunteers are dispersed in a valley amid the rumbling chaos of Western Washington University. Some are pulling nettle in the wetland, others are weeding educational gardens.

First-year Fairhaven student Kathy Kandiko finds Weston in the greenhouse looking intently at a clipboard, checking off lines on a messily scribbled to-do list.

After Weston relays detailed instructions, Kathy and a few volunteers head to the hothouse to pull out long stalks of cilantro, parsley and arugula.

Clearing out the beds takes longer than expected, and by the end only one volunteer remains. They bring the piles of produce over to a worktable, where triangles of late afternoon sunlight dance. Three remaining Outbackers gather around the table, munching on their bounty, discussing dandelion wine and their plans for the fresh cilantro.

Weston passes through and grabs a long stalk to-go. As he walks away, he rips into the cilantro stem like its corn-on-the-cob.

This is the Outback in 2019.

Birds chirp louder than scattered conversations; people work alone, breathing in the smell of the earth, allowing dirt to pack under their fingernails.

The Outback throws the occasional event, has a brand new bee apiary, and maintains the garden for educational, academic and community use. Students come not for the company, really, but for the peace the valley offers.

Though Outback Coordinator Kevin Harris often receives multiple emails a day inquiring about a community garden plot, many of the 30 raised beds will remain unused as summer approaches.

“There’s more interest than there is actual will or commitment… It’s like having a pet, you have to maintain it, you have to be committed to it,” Kevin said. “We don’t always have the ability to keep that interest.”

***

The Outback was created not long after the construction of the Fairhaven dorms in the late 1960s, at a time when Fairhaven flourished as an academic program focused on living and learning as a community through hands-on classes and educational freedom.

From week-long intensives that took students around the region for topical learning to a variety of independent studies and initiatives, the college defined itself as a place for people in search of connection and interdisciplinary understanding.

In the late 60s, students became interested in a valley between the Fairhaven stacks and the brand-new Buchanan Towers. The land had been clear cut, then flattened as machines hauled materials back and forth across the once vibrant landscape. A small creek was filled in with dirt and gravel.

Students didn’t know much about the history of the land, but they discovered the left-behind cabins of vagabonds June and Farrar Burn above the valley and turned them into a hang-out. At the cabins, they smoked pot and had long conversations about the state of the world.

Eventually, their meetings went beyond the cabins, to the desolate valley below.

“Every tree, every bush had been cut down. All the topsoil was gone. It was just clay,” former Fairhaven student and dean Roger Gilman said. “This scar on the land.”

Around Earth Day the students decided it was time to rewild the farm, to bring it back to its former glory.

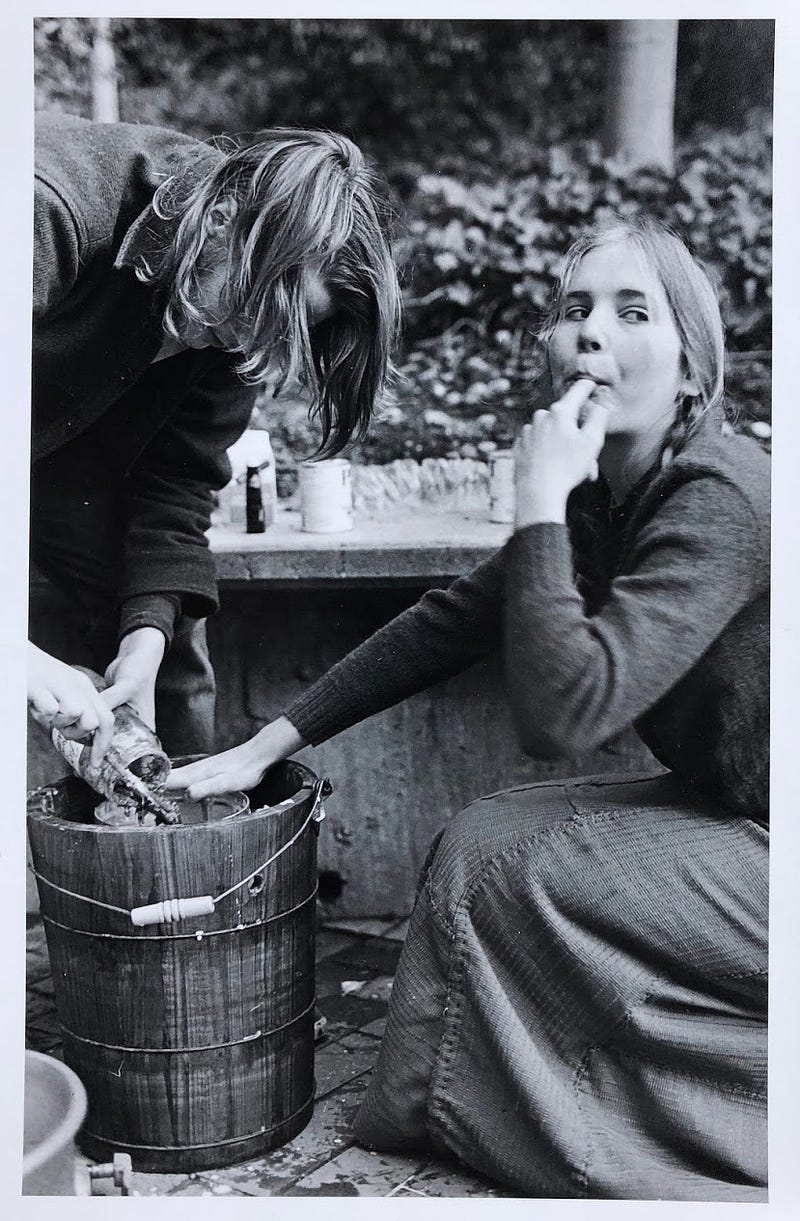

What began as a small group of friends and a cabbage patch turned into a 30-person operation with chickens, ducks, goats and pigs. Truckloads of dirt from the county were brought in. The creek was recreated. Trees were planted.

Within a few years, the valley was a wild place to be, as original Outbacker Tip Johnson said, “a going garden.”

For a while, Johnson alternated between living in his VW van and one of the Burns cabins. He made friends with students living in the dorms and they’d all come out to the Outback to play frisbee, dance, harvest vegetables and cook a big dinner.

“It flourished a little too much,” Johnson said.

It was a food network, one maintained by many and loved by all.

At the time, Johnson said there was a “captive audience of people willing to work” making it “quite productive for a number of years.”

There’s a saying that all good things must end, and in some ways the Outback did lose itself. By the turn of the decade, the once vibrant Outback community was spread across the country and the valley was left to new student leaders.

Pigs still roamed the valley. Students still lived in the cabins. But it wouldn’t last.

No one had ever really placed regulations on the farm, but that all changed abruptly when the university became self-insured.

Notices were given to Outback residents and the cabins were boarded up.

As the story goes, a wife of a university president was so disgusted by the Clivus Multrum composting toilet used by the cabin residents that she demanded it be torn down.

Not long after, Fairhaven Dean Dan Larner was pulled from his office by a student shouting “Someone is about to bulldoze the Outback!”

Larner raced outside, dressed professionally in a sport coat and tie. Sure enough, a bulldozer was pointed at the composting toilet. When his violent waving didn’t catch the drivers attention, he ran in front of it.

Larner managed to convince the driver to stop, and the tear-down was halted for a while. But not for long. The bulldozer eventually came back for the composting toilet and took the farm and one of the dilapidated Burns cabins with it.

“I was very sad that they tore the cabin down. It was never made that well, but it was historic,” Johnson said.

With the core of Outback-focused faculty and students gone, the farm was frequently inhabited by transients. The community crumbled. There was no one left to fight for it.

The invasive blackberries returned and the garden dwindled to dirt.

***

The university’s plans to use the land for dorms or a parking lot had always been clear, and even laid out in the master plan.

“It always kept coming up,” Johnson said. “But we got busy.”

As the decades wore on, the threat grew more imminent.

Students and volunteers stepped up every few years to fight for the farm when it seemed all hope was lost. Their repeated successes involved leading the farm into an educational realm for the broader Western community.

Saving the Outback killed the Outback, or at least, it’s original identity. Student volunteers weren’t friends but colleagues. They worked hard and made sacrifices.

“There was a real danger about a parking lot getting put in,” former Fairhaven dean Marie Eaton said. “It took a lot of effort and student and faculty meetings […] It was a very difficult job.”

Cori Garcia-Hansen, who spent much of her college years (1997–2001) fighting for the farm, worked nearly 60 hours a week on lesson plans and farm maintenance in order to convince the community of its worth.

She wasn’t the first, and she wouldn’t be the last.

The Outback received academic protection from the University in ’99. By 2006, the Outback was pulled under the Associated Students umbrella, guaranteeing greater funding and year-round paid student coordinators.

Since that time, the farm has “grown because there’s been more attention given to it” said Greg McBride, the assistant director of Viking Union Facilities and Outback AS program advisor. Paid positions have been added gradually, and the farm no longer has to reach into the broader community to get grants.

The AS offers valuable support structure to the Outback around programming and funding, McBride said. Though he admits that the student-created bureaucracy of the AS can often be frustrating for the Outback coordinators.

With more leadership roles, Gilman mentioned there was concern that there would be “a drop-off in a sense of collective leadership,” that students would not feel as if they had a stake in the farm.

When farm manager and Fairhaven faculty member Terri Kempton gives tours of the farm she makes sure to tell visitors, “This is part of your campus. Whoever you are, you know, come on in. The fences are for deer, not for you.”

The farm in 2019 is sprawling and successful, with a place carved in the curriculum of various colleges and enough food to stock campus food pantries.

Still, the perception remains, in strangers to the valley and volunteers, the Outback isn’t “mine.”

On the path to liberation, something was lost. Now, Fairhaven is trying to get it back.

***

Kathy can often be found toiling away in the garden. As a work-study employee, she gets paid for her time, but it’s evident in her cheeky grin and twinkling eyes that she would be here even without the promise of pay.

On a Wednesday in late April, Kathy heads to the forest garden to mulch some paths. The steep hill is full of herbs, bushes and vines that keep producing year after year. A grassy trail system weaves around each plot in a complex tapestry of green.

She works with a hula hoe, a stick with a stirrup-like attachment, and goes to work hacking away at the ground in an attempt to create a weedless trail before mulching. It’s a clear day, and the sun beats down on her back. It’s tiring work, but Kathy doesn’t stop.

She sheds a layer, rolls up her maroon sweats and continues.

Come fall, she’ll be joined at the Outback by nearly 50 Fairhaven students in the college’s first Living Learning Community.

Their coursework will be intrinsically tied to the Outback Farm. Each quarter of their first year, they’ll share one class together. It’s all part of a Living-Learning Themed Community focused on sustainable food systems.

Along with Fairhaven and Huxley College of the Environment course offerings, students will learn to grow food with coordinators at the Outback. They’ll live together in a stack close to the farm, which will be devoted to the program.

“We have the capacity for more Western students to be involved [in the Outback]. That’s clear. It is an underutilized resource,” Fairhaven Dean Jack Herring said. “But if we do this Living Learning Community for several years, we’re then going to have 100+ students who have had an intensive experience at the Outback.”

Dean Herring has made it his mission to bring Fairhaven College back to its origins as a residential college founded on a strong connection between living and learning.

Over time, Dean Herring said, Fairhaven has been decoupled, the Outback along with it.

Without these ties, the communities falter. Kitchens once bustling with hoards of Outbackers are now a stopping place for warming up Cup Noodles in the microwave.

The hope is that once again, a community will find each other in the valley. They will harvest cilantro, arugula and other veggies. And instead of heading separate ways, they’ll head back to their stack with the fruit of their labors in hand.