These Streets Weren’t Made for Walking

Bellingham is known for its gorgeous trails and passionate outdoor enthusiasts. But our roads weren’t made for them, or you.

Written by Ava Nicholas

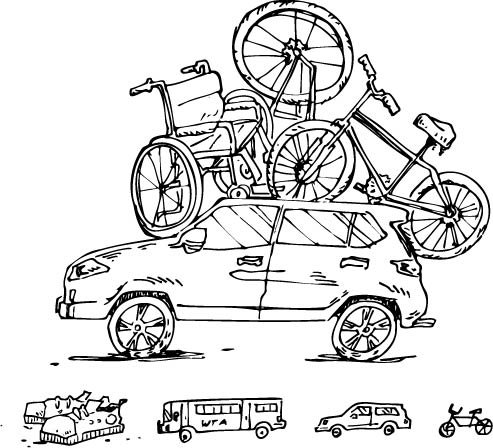

Illustration by Grace Matson

Racing down Lakeway Drive, an experienced cyclist bobs and weaves over the unkempt concrete. Nothing but a flimsy white paint line separates her from the fast, two-lane traffic at her side. Abruptly, her journey is cut short as her tire pops on a piece of wayward debris, and she is forced to trudge the rest of her route somberly, pushing her injured bike along. Although she doesn’t want to, next time, she’ll drive.

Tales of transportational and infrastructural woes are prevalent among Bellingham disabled residents or those who rely on alternative modes of travel. While Bellingham has a thriving community of bikers, hikers and walkers, ultimately, the city is mostly built around motor vehicles.

It can be difficult for a lone biker to work toward solutions for these tire-popping problems. Sonja Max and Jamin Agosti work to improve community standards for alternative transportation as board members for Walk and Roll Bellingham, an advocacy group focusing on accessible transportation and infrastructure local to Bellingham.

“I have appointments on Lakeway, and I'm hindered by that. I won't ride my bike over there,” Max said. “ I would rather get exercise, but I don't feel safe. So I'm gonna drive now. That's really frustrating.”

Roads like Lakeway can be intimidating to pedestrians, with fast, two-way traffic and no physical barriers protecting the sidewalk. There are no real protections for pedestrians from being struck by a careless vehicle. Even experienced cyclists might balk at traversing the loud, tumultuous road as they watch car after car whiz by, mere inches away.

Accessibility in infrastructure affects everyone, even unconsciously. Western Washington University’s Urban Planning Club co-president Jack Bengston is studying infrastructure for his future career, but seemed unconfident when discussing accessibility in the field. When asked whether he’s experienced any hindrances from lackluster infrastructure, he said, “As an able-bodied person, I have a hard time giving a realistic answer to that.” But a few questions later, Bengston noted how he would choose to bike to his local Fred Meyer, but felt unprotected on the way.

Argus Ortman, a Western senior, is a disabled Bellingham resident hindered by the city’s transportation. “I can't really catch the bus most of the time,” Ortman said. “And oftentimes there aren't seats open for me, as a person who lives on a cane basically all the time,” he said.

Even walking or taking the bus can be exhausting when the infrastructure is inaccessible. Plenty of the winding roads of outer Bellingham are constructed with poorly connected sidewalk systems on top of steep hills, and bus stops often don’t supply covered seating for waiting passengers. This forces people like Ortman to walk distances that leave them physically depleted upon reaching their destination.

No matter who you are, the most convenient mode of transportation has already been chosen for you. “If you're in a car, you can get to almost anywhere in any part of Western Washington for essentially free at any time of the day, safely,” Agosti said. “For the most part, the only category of people that can say that are people who can drive, want to drive, are willing to drive and can afford to drive.”

Even if you are someone who can drive, you may run into new circumstances where you would rather not sit behind the wheel. “Maybe you have accessibility challenges, maybe you have a kid in a stroller, maybe you just don't like driving, and you want to choose a more environmentally conscious mode of transportation, like a bus or a bike,” Agosti said. “If you want to do anything else, you have to make a ton of sacrifices,” he said.

Simple daily activities can be hindered by poorly structured roadways, like having to cross back and forth across the street to stay on a solid sidewalk, avoiding lengths of road with no pedestrian protections, all the while keeping a close eye on your excitable dog.

Emma Meilicke, an urban planning student at Western, has to stay extra vigilant while taking her pooch out for a stroll. “It’s the comfortability aspect,” Meilicke said. “I feel a lot more likely to leave the house if the sidewalk is a comfortable place to walk. Even an actual raised sidewalk, having a barrier between the sidewalk and the road, makes a difference.”

Whether you want to walk or prefer driving, person-centered infrastructure benefits those on both sides of the road. “Every one of us wants fewer cars on the road, even drivers,” Agosti said. “They need parking spots downtown. They want to not wait as long at a red light behind cars. It benefits every driver to have more people in the bike lane, and you know, on the buses, taking up less room on the streets for them.”

Parking in a smaller town like Bellingham can be a struggle with so many cars on the road, especially on weekend evenings in downtown. As the population grows, the city’s infrastructure has no room to build additional parking, compounding the problem. For people like Argus Ortman, fewer cars on the road would mean more parking spots closer to the places he needs to go. If the choice to walk or bike is easier to make, those who truly need to drive also benefit.

Think of your favorite spot in town. Perhaps it’s admiring the natural beauty of a local park, or shopping for a friend’s birthday gift from the craft vendors at the weekly farmer’s market on Railroad Avenue. “It's not going to be the Commercial Street Parking Garage,” Agosti said. According to Agosti, Walk and Roll recently implemented a bike valet at the farmer’s market, which regularly draws in 60 to almost 100 bikers who end up spending more time at local businesses.

The equivalent of over 50 cars worth of people takes up just three parking spaces. Bellingham is home to a variety of quality nature and community spaces, ones that would benefit greatly from a pedestrian-forward infrastructure.

“Bike and walk and take the bus downtown,” Agosti said. “Bike and walk and take the bus wherever you can, because people are looking at mode shift. Like, what percentage of the total trips taken in our area are by things other than cars, and seeing those numbers shift away from personal vehicles to bike, walk and transit trips helps show that there's demand for that type of infrastructure.”

Changes to Bellingham’s infrastructure are not insurmountable to make. Agosti and Max described work that Walk and Roll Bellingham is doing in conjunction with the Bellingham City Council to pedestrianize the downtown area. These changes are less likely to be made without the voices of residents showing support for these endeavors. One of the biggest barriers between more walkable streets, safer bike lanes and more accessible bus routes is locals actively supporting them.