In the fields, with the workers, against the system

Four women rebuild power through collective care that feeds and uplifts farmworkers who sustain our food system yet remain the most disadvantaged

Story and photos by Ava Meadows

Published February 03, 2026

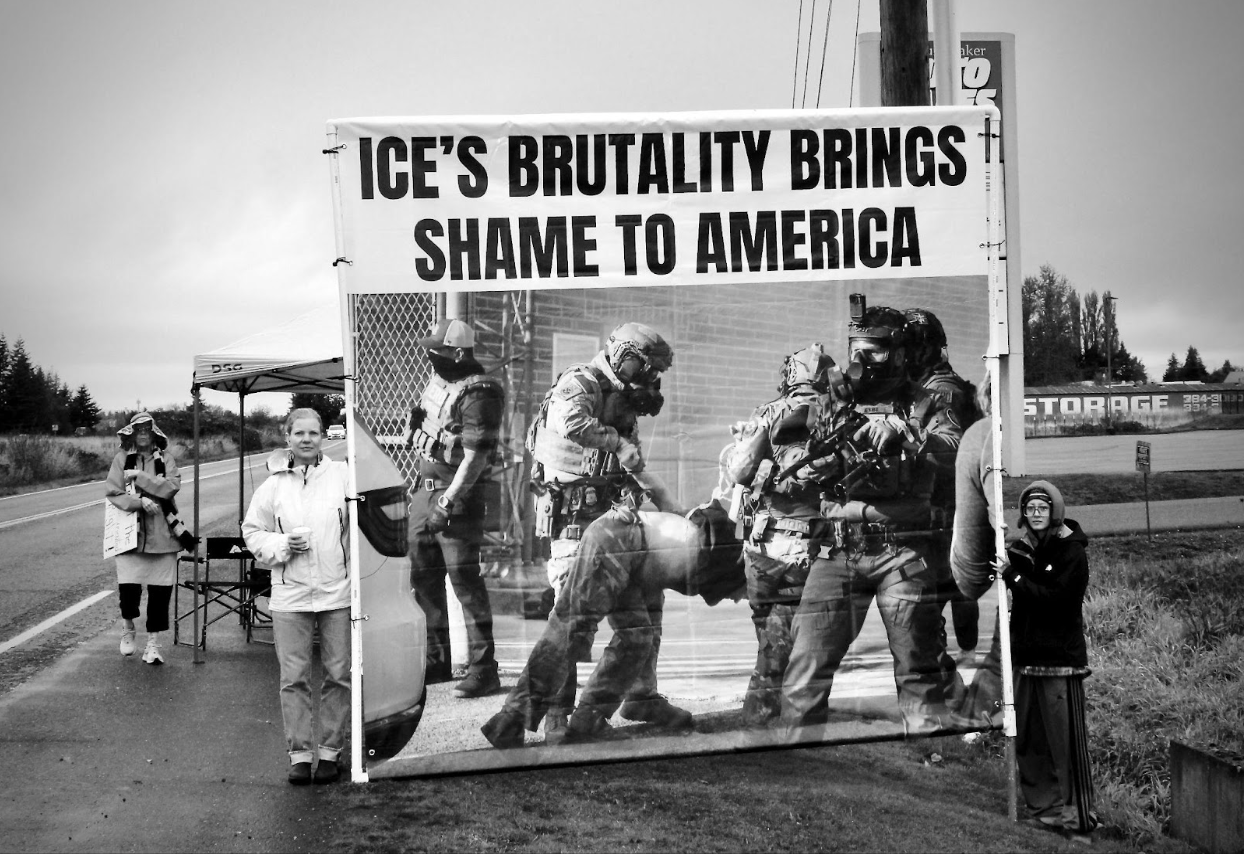

Liz Darrow (left) and Violet Ho (right) steady a ten-foot banner during Community to Community’s ( C2C) weekly protest outside the Ferndale Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) facility.

At 4 p.m. on a late-October Friday, the shoulder of the Ferndale highway felt raw in the way pavement gets when the cold settles. A sweet, older man with a windburned face stood alone trying to wrangle a 10-foot banner slapping against his legs. The image on it was of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement officers forcing a man to the ground.

Protesters clustered shoulder to shoulder, their fluorescent poster boards click-clacking like restless teeth. Cars hissed by — honks of support drowned out by spit from a rolled-down window, the flick of a middle finger, the blast of a truck skimming too close.

Liz Darrow from Community to Community (C2C) poured coffee from a steaming thermos, pressing warm cups into cold hands.

C2C is a Bellingham-based, farmworker-led organization built by people traditionally stripped of power: immigrants in berry fields, single mothers juggling shifts, working-class residents scraping for rent.

As Darrow stood on the wet shoulder, the space beside her felt newly hollow. “Before Lelo was deported, the clarity of what we were doing was a lot easier,” she said.

Alfredo “Lelo” Juarez Zeferino had been driving his partner to the tulip bulb fields on a March morning when unmarked vehicles eased in behind them. Blue lights cut through the fog; the gravel under Lelo’s tires crackled as he slowed to a stop. ICE officers stepped out and arrested him on the spot, transferring him to the holding facility in Ferndale — the very place C2C protests each Friday.

“I’ll never forget standing in my kitchen at 6 in the morning and getting that call,” Darrow said. “Lelo is family; we've known him since he was a little kid.”

After one day in Ferndale, he was moved to the Northwest Detention Center, where four long months inside drove him to accept voluntary departure and return to Mexico. Guillen later read from a letter he wrote while in custody, saying that “justice in the NWDC” meant sleeping on floors and waiting days for food that never came. “Now that I am here, I have seen just how bad things are,” he continued.

His absence left a weight on the work. Cross-border organizing, Darrow said, is “complicated and dangerous and expensive,” and she believes ICE took Lelo to slow them down — and in many ways, it did.

“It hurts so much,” she said. “We’re less bold now — but we still have to keep going.”

That persistence is built by the careworn hands of four badass women who know how hard it can be to put food on the table. Rosalinda Guillen, Liz Darrow, Brenda Bentley and Tara Villalba anchor C2C’s work in their lived realities.

As the founder of C2C, Guillen’s story begins long before the organization started. Born in Texas, raised in Mexico and brought to Washington at age 10, Guillen spent her adolescence in the migrant farmworker camps of La Conner. Her hands were calloused and cracked with soil while rows of spinach and tulips stretched toward a sun that never seemed to rest. Those fields taught her the politics of exhaustion, the quiet dignity of labor and how the body bends with the land until the two nearly blur.

“The people who aren’t already well taken care of love to dream about a better world,” Darrow insisted. When Guillen founded C2C in 2003, she built it from the unromantic knowledge of someone who’d spent a lifetime watching family labor past the point of exhaustion. Darrow, meanwhile, arrived from a different landscape: Mount Elizabeth, a conservative, working-class town in Washington where money was scarce, and anger was common.

“My background is a person impacted by poverty in a large family, and how that changes the decisions people make,” Darrow said.

In that kind of deprivation, every choice was a negotiation between what could be spared and what couldn’t.

At 18 years old, Darrow carried a child and a dream in opposite arms. She had been studying biology at the University of Oregon, tracing the logic of cells dividing while the living reality formed inside her. “I still think biology is fascinating,” she said, “but then I had this real-life human being, and that’s a different kind of process that feels more creative.”

As a teen mother, she learned what it meant to make do. Darrow had moved to Bellingham in 2000 so her sister — then a Western Washington University student — could help her stay afloat. “I really related to the very basics of what it costs to raise a family and how that struggle is invisible from the food system,” Darrow said.

By 2009, her son was in grade school when a major ICE raid struck Bellingham. “That was my first time seeing how it impacted my kids’ classmates and their families,” she said.

Protests rippled across the city in the days that followed. Darrow’s son was young, and the crowds felt unsafe, so she stayed back. From afar, she watched movement art rise into the streets, banners billowing above the noise. “It made me feel not just welcome, but motivated,” she said

It was the beginning of an understanding that art could make politics feel accessible.

That understanding takes shape in the work of Brenda Bentley, C2C’s arts department coordinator, who creates visuals meant to halt people mid-stride: signs weathered for long, wet days and hand-painted banners held steady by tired hands. When a march comes through, people are taken aback. “They stop, and they look at the signs,” Bentley said. “That’s what we want them to do.”

Handmade signs remain part of the visual language of C2C’s weekly protests.

She grew up in late-1970s Los Angeles during the first wave of punk — “before that whole macho thing came in.” Smog hung low, a secondhand haze curling around a half-asleep, half-feral city alive with kids who had nowhere to be but together. “Women were just there and leading,” she said. “We didn’t even think about it; it was our space.” Yes, the music was loud — but it was what the noise made possible: a space for “nonconformist awkwardness.”

Bentley was raised in a one-bedroom apartment that held more women than furniture. Her grandmother worked nights; her mother — a young hippie — moved with stubborn spunk. In that matriarchal house, threadbare but alive, there was no man’s voice to wait for at the door.

“I wasn’t answerable to any patriarchal figures,” Bentley said. “They watched me grow up and allowed me that expression.” Refusing to wait for permission became its own art form.

“It was designed to say, ‘I am not a part of this consumer, homogenized society,’” Bentley reminisced with the faint nostalgia of sweat-slick nights that smelled of warm asphalt and teenage angst.

Her punk-bred sensibility rises from the same anti-hierarchical ground that keeps C2C steady. “We’re not office people,” Bentley laughed. “We don’t want to replicate a capitalist structure.”

This manifests in the work of agroecologist Tara Villalba, whose life began in the kitchen heat of the Philippines, where she started working at just 12 years old. When her family moved to the U.S., the labor followed: underpaid restaurant jobs, dishwashing shifts, long days that smelled of garlic, bleach and sweat.

Years later, after finishing school, Villalba carried that lived experience into coordinating C2C’s Tierra y Libertad Farm.

Tierra y Libertad — Spanish for “Land and Freedom” — is the farm’s cooperative agroecology project in partnership with C2C that helps to provide a training and practice place for the organization's youth program. Teenagers, mostly the children and grandchildren of farmworkers, arrive in the gray morning light, pulling on dew-soaked gloves to haul compost. They come for the paycheck, but also for what school doesn’t offer: connection to the land, family and their own sense of usefulness.

“We need the children of farmworkers to want to be farmworkers,” Darrow said. “To understand how sacred that is.” In classrooms, they’re told their parents’ work is something to outgrow, not to inherit. “It’s really a beautiful thing to be like, ‘This is enough, this is what you love, and we, by the way, need this.’”

That kind of reclamation — of work, of pride, of place — exists because four women refused to accept the world as it was handed to them. Their stories aren’t tidy parallels, but they converge in the same place: an insistence that dignity is something we build together, one small act at a time.

“When you learn what solidarity really means, it means turning up not just once, but again and again and again,” Bentley said.

It sounds simple, almost soft, until you see what it actually requires. It asks people to show up on cold highways and in crowded kitchens, in fields at dawn and in meetings that drag past dinner. It asks them to risk something. Sometimes everything.

Still, these women keep at it. Not because the work is easy, or safe or ever guaranteed to win, but because they know nothing changes unless ordinary people show up again and again and again.