Creating safe spaces for all

How making a conscious effort to understand the experiences of those around you benefits everyone

Story by Sophia Raymond

Published Feb. 03, 2026

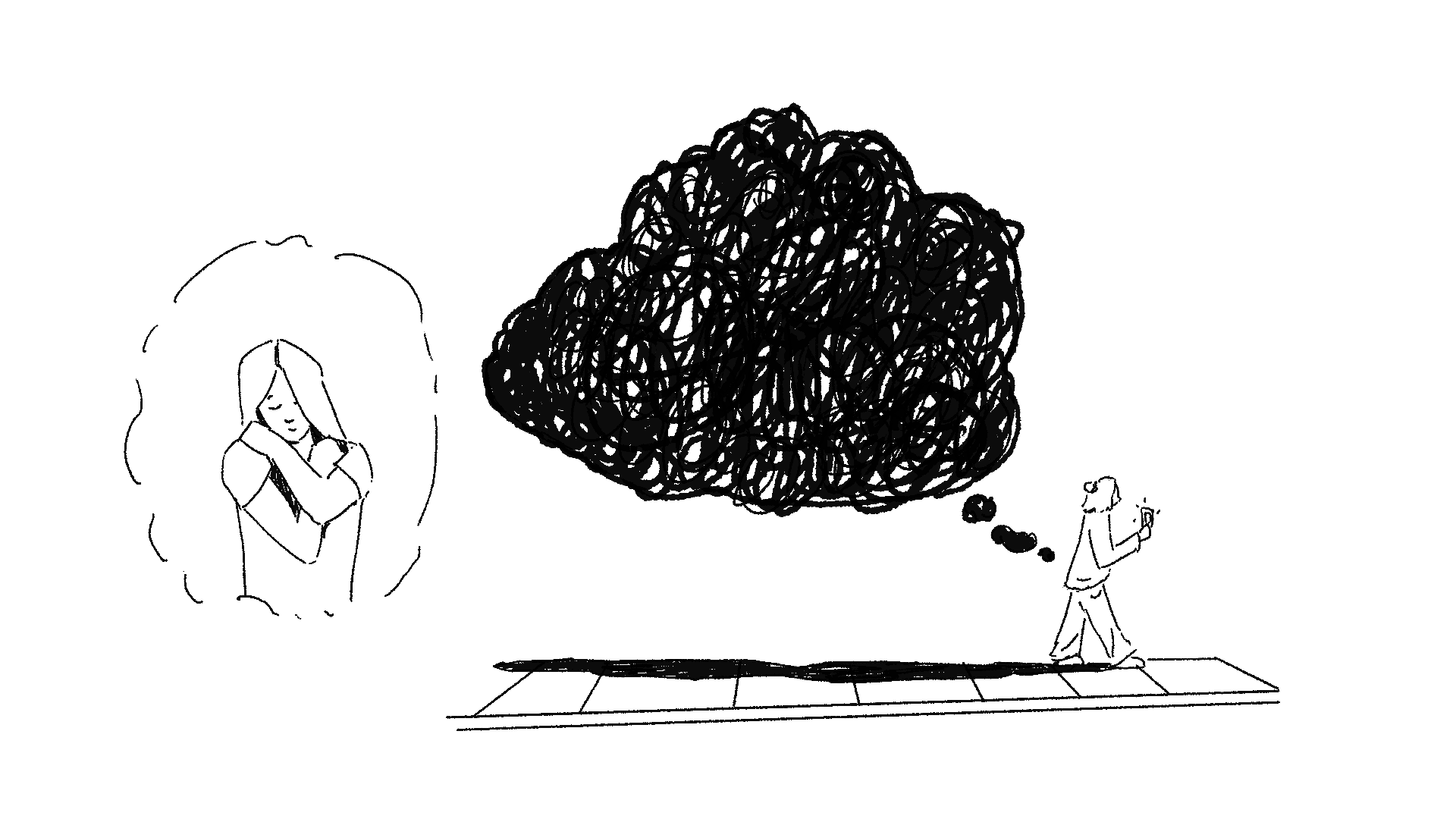

Illustration by Royce Alton.

“You’re going out dressed like that? You should cover up.”

“Did you bring pepper spray? Make sure you walk in well-lit areas.”

“He said that because he likes you. Be polite, smile and move on.”

“Be safe. Text me when you get home.”

Every time a woman leaves the house, they must consider everything in terms of safety. What they’re wearing, where they’re going, who’s going to be there — the list goes on. Even taking an Uber or having food delivered to their home can feel like an at-risk situation as a feminine-presenting person.

Women often feel the need to be on high alert, riddled with the fear of assault and harassment. Their hearts may beat rapidly when someone follows too close behind on the sidewalk, their eyes darting around for possible escape routes. They may frantically search for pepper spray just in case they have to defend themselves.

Elias E., 19, a second-year Western Washington University student, felt this need for vigilance growing up as a feminine-presenting person in Texas. Since coming out as transmasculine, E.’s perception of safety has shifted; they’ve been able to walk more freely — and it feels unsettling. When they presented more feminine, they took higher safety precautions in public. After transitioning and being able to stop taking these precautions, they developed a sense of agoraphobia, a fear of being in places where escape is difficult. E. felt uneasy not needing to take these precautions, especially since that cautious mindset weighed on them for so long.

Carolyn Harmon, a recent Western graduate, has adjusted her sense of awareness for different reasons. She grew up in a small town in Montana, where her parents instilled the idea of “stranger danger.” Since moving to the more bustling city of Bellingham, Harmon has become more cautious going out, especially in unfamiliar spaces. She feels safer with more people around compared to being one-on-one with a stranger, saying it feels like a “safety net.”

“Hopefully not every single person here will let something bad happen to me,” Harmon said.

Walking with caution in public is a familiar feeling for many feminine-presenting people, often being told to “smile” by strangers while walking down the street or getting called “sweetheart” by an older man at work is routine behavior experienced by women. According to a #MeToo National Study of Sexual Harassment and Assault in the United States from 2024, more than three in four women have experienced verbal sexual harassment — the most common form of harassment — compared to one in four men.

The responsibility of being safe and prepared for these situations is heavily put on women and girls, who are the most targeted group. For E., they’ve always felt sexualized around men, especially in their early teens.

“I never really felt like we were both humans,” E. said. “Boys are crazy, and it kind of felt like I was a little sheep around hundreds of wolves and they were going to get me.”

Growing up, E.’s mother taught them to have good manners and to respect the men in the household. They were told not to challenge their father in arguments and to use a calm, proper lady’s voice. As a young teen, E. was blonde, thin and usually wore jeans with a t-shirt. They developed curves in high school, which drew unwanted attention from overly “nice” men. About five years ago, they began socially transitioning to a man.

“I think one of the reasons I was able to realize I was trans so soon is because I was getting so sexualized,” E. said. “It made me really consider my gender and sexuality more than I think I would have been if I wasn't in that situation at that age.”

E.’s experiences are not unique. According to a #MeToo National Study, oversexualization and harassment are the harsh realities for many young girls, with one in five women in the U.S. reporting having their first experience with sexual assault or harassment before age 13. This anticipation of harassment sits in the back of every girl’s mind, but what about boys?

Based on their own experiences, E feels that masculine-presenting people carry fear with them differently than those who are feminine-presenting. Instead of sexual violence, they’re more afraid of physical violence and crime. “I feel like I'm less likely to get raped and abandoned in the street, and more likely robbed,” E. said. “It doesn't feel like I'm being hunted, it just kind of feels that there's people around me.”

Today, E. has bright red buzzed hair, face piercings and often wears a chest binder under baggy clothes. Although their fears shifted toward crime, this change in appearance has also impacted the paranoia of others. Now, instead of being worried about their own safety, E. must be aware of how their masculine appearance intimidates the women around them — especially at night.

“She was in a super sparkly green dress,” E. said. “I was going to compliment her when I realized that in my big jacket and my binder and fully ‘masced’ up, I probably look like a threat to this sweet girl.”

Understanding how you’re perceived by others is the first step in creating safe spaces for those around you. Liz Stuart, the assistant director of outreach and health promotion at Western’s Health Promotion and Resilience Office, said that once you acknowledge your social status in your community, you can use your position to make an “effort to try to equalize that power.”

“The issue is that privilege just gives us tunnel vision,” Stuart said. “We won't see it.”

Once you recognize your own identity, take time to learn about those around you with differing identities. Stuart emphasized the importance of small interactions. “You can be vulnerable and say, ‘I don't know how to do this, but I know that women don't feel safe a lot in male spaces or with men around,’” Stuart said. “Then ask, ‘What would be helpful to make things feel safer for you?’”

Being an ally is about listening, learning and sticking up for those around you. When Harmon was at Rumors Cabaret, an LGBTQ+ nightclub in Bellingham, one of her friends was continuously pursued by a masculine-presenting individual. The interaction only stopped when Harmon’s boyfriend “physically put himself in between them.”

While these situations are inevitable, the Rumors staff try their hardest to prevent these encounters from happening. According to Ezra Wagoner, the bar manager at Rumors, safety is their top priority.

Before entering Rumors, guests scan their ID using Patronscan, a system that flags the names of people who’ve been banned from the club, making it easy to weed out any recurring instigators. Security also takes their own assessment of people before allowing them in, making sure they understand Rumors is an inclusive space.

“We try really hard at the front to have a brief conversation to kind of gauge someone,” Wagoner said. “Just making sure that they're not there for the wrong reasons.”

Once inside, two or three staff members vigilantly observe the crowd for anyone experiencing or creating an uncomfortable situation. Wagoner said the staff takes every complaint seriously, no matter the severity.

“If they're saying someone's making them uncomfortable, we're not questioning them, we just ask for an explanation of the situation,” Wagoner said. “We go address it with the person as opposed to being like, ‘Oh, you must be making this up.’”

From behind the bar, Wagoner’s noticed “peer corrections” between customers. If someone’s making another person uncomfortable, they get called out.

Some don’t realize they’re making others feel unsafe until it’s pointed out to them. “I've had to have so many conversations with my cis man friends and say, ‘Hey buddy, don't be an asshole,’” E. said.

Harmon has said similar statements to acquaintances, usually when they’re intoxicated. “They’re not quite aware that they're maybe in someone's personal space,” she said. “I have had to be like, ‘Maybe you don't need to be hugging someone like that.’”

Occasionally, Wagoner has to remind masculine-presenting customers that people are there to have fun, not to find someone to hook up with. “People are either here with their friends or, you know, lesbians exist,” Wagoner said.

Instances like these illustrate the lack of education on this topic and highlight the need to include everyone in conversations surrounding safety and consent.

“It's harder for folks to see why they would engage in a conversation about something that doesn't feel like it impacts them,” Stuart said.

To create and promote these safe spaces on your own time, Stuart recommends starting by recognizing your identities and acknowledging the power dynamic between yourself and others. Then you can ask those around you what they need and how you can be a better ally in terms of safety. Lastly, accept feedback with open arms, learn from those conversations and implement those practices.

“If you're not getting it right and you're making mistakes, invest in making a change and keep trying,” Stuart said. “Don't give up. We have to be persistent.”