The WHOLE picture

Funding the people and passion behind Western’s largest basic needs pantry

Story and photos by Franny Vollert

Published Jan. 24, 2026

A Western student takes food from the WHOLE Pantry fridge on Oct. 27, 2025. The pantry serves anywhere from 1,500 to 2,000 students in a regular week.

It’s noon on a Thursday in Bellingham. The temperature is in the low 50s, but wind and rain are working together to make it feel like 40. Tulea Enochs doesn’t need a jacket, though. She stays warm by heaving 50-pound bags of rice from a minivan up to the Western Washington University Viking Union loading dock, while workers push dollies back and forth into elevators, stocking markets and the dining hall three floors above.

“This is the biggest order I’ve seen you bring in on a Thursday,” says Wil Guilfoyle, one of Enochs’ few volunteers. He hands items from the van up to Enochs, who loads the boxes and bags onto rolling carts.

The two work fast and efficiently, relieving the old Ford Freestar of hundreds of pounds of prepackaged and bulk items — ramen noodles, rice, oats and canned soup. Enochs describes the van as being “dangerously low to the ground,” bogged down by the weight.

“Now you know why I’m always flustered and out of breath,” she says.

An order of this volume is unusual for a Thursday, but today isn’t normal. While Enochs works, she chats with Guilfoyle about the volume of students coming through the Western Hub of Living Essentials (WHOLE) Pantry, located on the fourth floor of Western’s Viking Union. They’re expecting an additional 500 students this week, on top of the estimated 1,700 who have already visited since Monday morning.

The surge isn’t random. On Nov. 1, 2025, the Trump administration suspended Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) funding amid a government shutdown which became the longest in U.S. history, lasting 43 days. Roughly 42 million Americans were left without stable food assistance, turning to local food banks and pantries for their daily and weekly sustenance.

WHOLE Pantry volunteer Eli Moore looks for bulk items to repackage in the storage room on Nov. 4, 2025. Moore volunteers with the pantry twice during the regular week and during the weekend.

Once the food from Enochs’s visits to Costco and the U.S. Food Chef’Store is stacked high onto rolling carts, she and Guilfoyle venture up to the fourth floor to begin stocking the WHOLE Pantry’s storage room. The storage area measures roughly 8 by 10 feet, but standing room is even smaller, with large metal shelving and an industrial-sized refrigerator taking up much of the high-traffic space.

They talk while they stock, and within 10 minutes, everything is off the carts and sorted onto the shelves. The room is filled to the brim, and it will all be gone in less than a week.

Last fall, the pantry, which provides no-barrier access to food and hygiene products for students in need, served roughly 600 students per week. During the first week of the fall 2025 quarter, the pantry served around 1,400 students over three days. During the third week of October, the pantry saw around 2,000 students. These numbers are estimated using a tracker in the doorway of the WHOLE Pantry, which counts when a student walks in and when they walk out.

Eli Moore, a fourth-year at Western, is one of those students. In addition to using the WHOLE Pantry’s no-barrier resources, they also volunteer twice a week, repackaging and stocking food.

While they hoped to gain work experience through volunteering, Moore said that being under financial stress made them especially appreciative of the pantry’s resources, creating an added motivation to contribute to its success.

Around 3 p.m. on their volunteering days, Moore heads down to the storage room and begins repackaging dry bulk goods — rice, pasta, beans, oats — to stock the pantry’s shelves. The items they spend the most time packaging, Moore said, are generally among the most unpopular. “Millet, I know it’s one of those dry grains or something,” they said. “I repackaged a bunch of those a while ago, and there’s still a bunch left.”

By 5 p.m., when it’s time for Enochs to head home for the day, anywhere from 200 to 400 students will have taken advantage of the resources provided by the WHOLE Pantry.

Six months ago, Enochs was working as the administrative assistant to the Centers for Access, Community and Intercultural Engagement at Western. In June, she was laid off without receiving any official communication until a human resources meeting discussing university restructuring. During the meeting, she said, it was implied that she was not to return to campus.

When speaking about her layoff, Enochs describes the experience as humiliating and dehumanizing, adding that she will always remember it. After two months of unemployment, she was brought into Western’s Basic Needs Hub as a full-time WHOLE pantry coordinator.

“It’s been wonderful to again land in an area where I feel like I can help people and help them more directly,” Enochs said.

Part of Enochs’ salary is funded by the Student Food Security Fee, which is added to the tuition of students taking at least eight credits. The $4.50-per-quarter fee was implemented by the Board of Trustees on Oct. 18, 2024. Before the board’s vote, the fee was proposed by the Associated Students and subsequently voted on by the student body.

Tulea Enochs wheels a cart of collected food into the WHOLE Pantry storage room on Oct. 27, 2025.

According to Adam Lorio, Western’s Associated Students governance advising program director, the fee amount was determined based on several factors. Funds for a coordinator position, as well as purchasing the products that will eventually fill the pantry’s shelves, were both under consideration.

Prior to the fee’s implementation, the pantry relied solely on charitable monetary donations and food donations, since state or university funds couldn’t be used for food purchases. There was simply not enough recurring money to bring in a full-time coordinator.

Currently, Enochs describes herself as being in a “project position” rather than a permanent one, as the Student Food Security Fee faces a termination date of June 2027.

Lorio said this is typical of referendum fees, or fees proposed by students. During spring 2027, students will have an opportunity to vote again on the Food Security Fee, this time, on whether to retain it.

“Most of the fees that are voted on by students persist for quite a long time,” Lorio said. “It’s rare that those fees get canceled or left to the side.”

Currently, the WHOLE Pantry is operating with a budget of about $130,000 per academic year. Enochs’ rough predictions when she began as the pantry coordinator determined that this number would need to sit around half a million to meet the increasing need from students. Now that she has been in the position for a few months, she re-estimates that $380,000 to $420,000 per academic year would be necessary.

“We’re going to keep trying to make every dollar stretch as much as we can,” Enochs said. Some of these money-saving efforts include buying food pantry items in bulk and repackaging them. While pre-made meals are more convenient for students, they’re a less cost-effective and sustainable option.

Enochs recognizes that while raising the Student Food Security Fee, even by $1 per quarter, would significantly increase their purchasing abilities, students face many other costs.

“While this fee is very small, when it is combined with other fees that students have to pay, it starts to become a ‘death by a 1,000 cuts’ situation,” she said in an email.

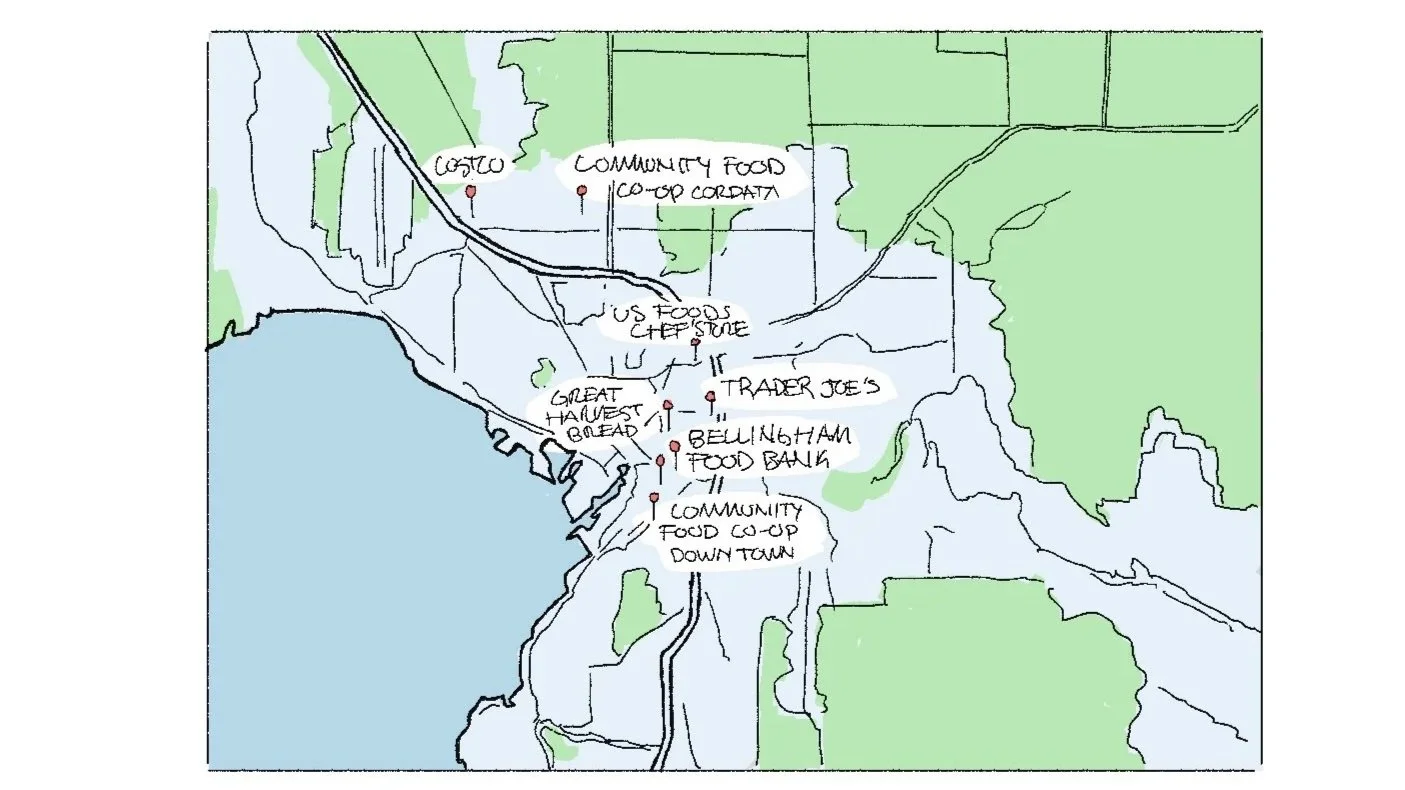

A map of the organizations that the Food Pantry sources from. // Illustration by Royce Alton

More than half of students in Washington state experience basic needs insecurity. The rate of students experiencing food insecurity, specifically, has increased by 14% since 2022.

Among Western students who responded to the WSAC survey, 44.5% reported food insecurity.

Enochs said that she has met with multiple external food banks in the area, including the Bellingham Food Bank, and usage has been increasing across the board.

Bellingham Food Bank Executive Director Mike Cohen said that since 2021, visitation has increased by roughly 300%.

The food bank serves 5,000 households per week. With around 10% of Whatcom County residents relying on SNAP benefits, Cohen said that food banks can’t make up for the gaps that potential cuts to that program will create. More broadly, people are motivated to use food bank services by the increasing costs of living.

“Inflation at the grocery store is very real,” he said. “All those things that we need to spend money on to get through our days and weeks continue to grow, but most people’s paychecks or benefits aren’t growing at the same pace.”

Meanwhile, the WHOLE Pantry machine keeps on chugging, serving its hundreds of students per day. Numbers on the tracker continue to tick as students walk in and out, and volunteers organize shelves in the storage area.

As Guilfoyle heads out, he calls to Enochs, “See you next Thursday!” when he’ll come in and do it all over again.