The Practice of Making Each Other Visible

How a small abolitionist collective in Bellingham is using letters, artwork and community pressure to confront the county’s plan for a $174 million jail

Story and photos by Ava Meadows

Published Jan. 24, 2026

Mold streaking down the exterior wall of the Whatcom County Jail. Photo by Ava Meadows.

Meadow Lundstrom has learned to open the envelopes slowly. The paper arrives creased and thinned at the folds, its corners softened by too many hands — first written in a cramped cell, then screened under harsh inspection lights, then pushed through Whatcom County’s sluggish mail stream.

Held in his hands, the letter feels quiet. The place it comes from is not. Some imagine jail as a world apart: a row of faces behind glass, fluorescent lights humming, the shuffle of orange uniforms. A place for the irredeemable — those who supposedly belong somewhere else, sealed off to keep “them” from “us.”

Letters disrupt that distance.

Through Unchain Whatcom, a Bellingham-based abolitionist collective, Lundstrom joined a network of correspondents that act almost archaic in their tenderness with pen and paper, envelope and stamp. The program pairs community members with people inside the Whatcom County Jail, asking strangers to witness one another’s lives.

The reality that arrived in Lundstrom’s mailbox — tender, ordinary and painstakingly human — contradicted everything he’d grown up hearing at home. “My parents have very close-minded views on my participation in this program … They see incarcerated people as dangerous and violent,” he said.

What he found instead were deliberate offerings of time. One pen pal sent Lundstrom an ornate cross, its graphite darkened where his hand must have lingered. “It takes a lot of time. It takes a lot of energy,” Lundstrom said. The drawing wasn’t made for a gallery; it was a small act of presence, a way of saying: I’m still here.

Early on, one letter carried more weight than any envelope should have to hold. A pen pal described losing a close friend to suicide inside the jail — a story so vivid that Lundstrom reread the words, the page trembling slightly between his fingers.

According to the Whatcom County Justice Project Needs Assessment (2022), nearly 58% of people in the jail need mental health treatment, and 61% struggle with substance use. In a facility lacking adequate therapeutic spaces, suicide is a predictable outcome of a county unprepared to care for the people it confines.

Lundstrom still struggles to talk about that letter. “It took me a while to formulate a response,” he said quietly. “I don’t even know if there’s something you can say that truly —” He paused, looking down at the table as if the words might be hiding there. “— I don’t know.”

The letters are fragile things, but they’re also a kind of art — made under constraint, moving slowly, insisting on connection in a system designed for disappearance. That insistence is where Lundstrom began to understand abolition not just as a political idea, but as a creative practice built through relationships.

A Jail Already in Crisis

Through the letters Lundstrom exchanges every week, the physical reality of jail intrudes constantly.

Stationed on a downtown block you’ve probably driven past without noticing, the jail’s exterior resembles a neglected office building. Reports included in The Front (March 2025) describe hallways the color of stale oatmeal, air thick with sour dampness and ceilings where mold blooms across leaks patched so many times the paint puckers like damp paper. There are no counseling rooms and no dedicated mental-health spaces — only two padded cells deputies refer to as “drunk tanks,” each barely large enough for a person to pace in circles.

In a jail built like this — windowless, grayed, suffocating — it isn’t hard to understand how someone already struggling could reach a breaking point. The friend Lundstrom read about didn’t die in a vacuum; he killed himself inside the county’s own corridors.

Narrow, security-screened windows line the upper floors of the Whatcom County Jail, streaked with years of grime and weathering. Photo by Ava Meadows.

The conditions described in the letters make it clear that the facility is already stretched thin. So when county officials began proposing a new building, Lundstrom wasn’t reassured. “With the expansion, that’s only going to get worse,” he said.

Nearly 98% of people inside the Whatcom County Jail are legally innocent at any given time — held not by conviction but by court delay. Cash bail falls hardest on those with the least, with 64% of incarcerated people saying their detention was prolonged because they couldn’t afford bail.

Washington’s Criminal Rule 3.2 allows judges to release pretrial inmates unless the court finds clear evidence that they pose a danger to the community. Yet Cascadia Daily News found that judges rarely use those options at all. The result is a jail filled not with the violent, but the poor.

A $174 Million “Replacement.”

In November 2023, voters narrowly approved a countywide sales tax to fund what officials called a “jail replacement” — a $174 million construction project marketed as trauma-informed. It was the county’s third attempt in a decade. A 521-bed proposal failed in 2015; a 480-bed proposal failed in 2017. After those defeats, officials avoided naming the bed count during the 2023 campaign.

That vagueness now looms large.

In July 2025, county officials acknowledged the new facility could range from 400 to 700 beds — a ceiling nearly double what voters rejected in 2015 and 2017.

County Treasurer Steven Oliver has also urged caution. “The proposed jail is simply larger than we can afford,” he told Cascadia Daily News (Sep. 2023). Anything exceeding $100 million, he warned, risks destabilizing the county budget for years.

Unchain Whatcom calls the plan what they believe it is: a mega-jail, warning on its website, “If they build it, they will fill it.” They argue the current facility’s deterioration has been strategically neglected to justify expansion.

History suggests this concern isn’t unfounded. When the downtown jail opened in 1984, it was designed for 148 people. Within two years it exceeded capacity and has remained overcrowded since. Officials responded by double-bunking single cells and later adding an off-site Work Center with roughly 150 more beds.

When neighboring Skagit County built a larger facility, its incarceration rate jumped 30% despite no rise in arrests. To Unchain Whatcom, this proves that bigger facilities don’t relieve pressure so much as create room for more of it.

What the County Says

Lundstrom knows how radical abolition can sound to people hearing it for the first time. “You kind of have to ease into it,” he said.

County Executive Satpal Singh Sidhu, however, begins his explanation in a different place. “A long time ago, somebody stole somebody’s goat,” he said. “That’s when the jail started.” From there, he drifts into analogy: a child stealing marbles, a parent sending them to their room. “That room is a jail,” he said, smiling at the simplicity of it. To him, imprisonment sits on a long continuum of how societies establish boundaries, how families respond when rules are broken, and how separation becomes a tool for restoring order.

Whatcom County’s Justice Project depends on preserving that tool. Sidhu rejects calling it a jail expansion, insisting it is simply a “replacement” for a deteriorating building. “The jail is overcrowded not because our laws are punitive, but because it’s falling apart,” he said.

Sidhu points to a case from about a decade ago: a man who walked into a Bellingham bank, declared a robbery, and waited calmly for police. He told officers he did it because jail was the only place he could reliably get food, shelter and medical care. I asked if that was the kind of community he wanted to live in — one where a person would rather be caged than live free. “No, no, no, no,” Sidhu responded quickly. “You, as a taxpayer, are willing to fund the services inside the jail, but you are not willing to pay the tax to fund them outside.”

What the Community Actually Does

Sidhu’s framing implies that neglect is the natural posture of the public — that people “out here” refuse to care for those “in there.”

Mutual aid throughout the county tells a different story.

Earlier this year, Unchain Whatcom helped raise $500 to bail out a Lummi man who had spent a year in pretrial detention. By the time most of his charges were dismissed, the harm was already done — he had endured racist targeting inside the jail and had been separated from his mother, for whom he was the primary caregiver.

When presented with racial disparities, Sidhu dismissed them outright: “We do not have any laws or train our police to, if the person is Indigenous, arrest them.”

The county’s own data complicates that claim. Native residents make up 4% of the Whatcom population and 14% of the jail population. Disparity doesn’t require a written policy; it only requires a system that produces unequal outcomes, and leadership willing to explain away those outcomes.

Imagining Something Else

When people confront these realities, the next question is inevitable: If the system is so harmful, what should replace it?

Even mentioning abolition can trigger an eye roll or anxious laugh —“But how would we keep the community safe?” That reaction isn’t malice; it’s the product of the narrow imagination officials have taught the public to accept.

To abolitionists, imagination is not naïveté. It’s a refusal to mistake what exists for the limits of what’s possible.

For Unchain Whatcom, the pen-pal letters are the most tangible expression of reimagined safety. “The people I’ve talked to describe the pen-pal program as one of the only things they have to look forward to,” Lundstrom said. “It’s incredibly humanizing.”

Anthropologist Orisanmi Burton told Truthout in an April 2022 interview that the slowness of letters — the waiting, the handwriting and the emotional labor — creates a contemplative space digital communication can’t replicate. He calls it a “mutual investment of time,” an imaginative field where people begin shaping futures they’re not yet allowed to inhabit.

Art as Evidence

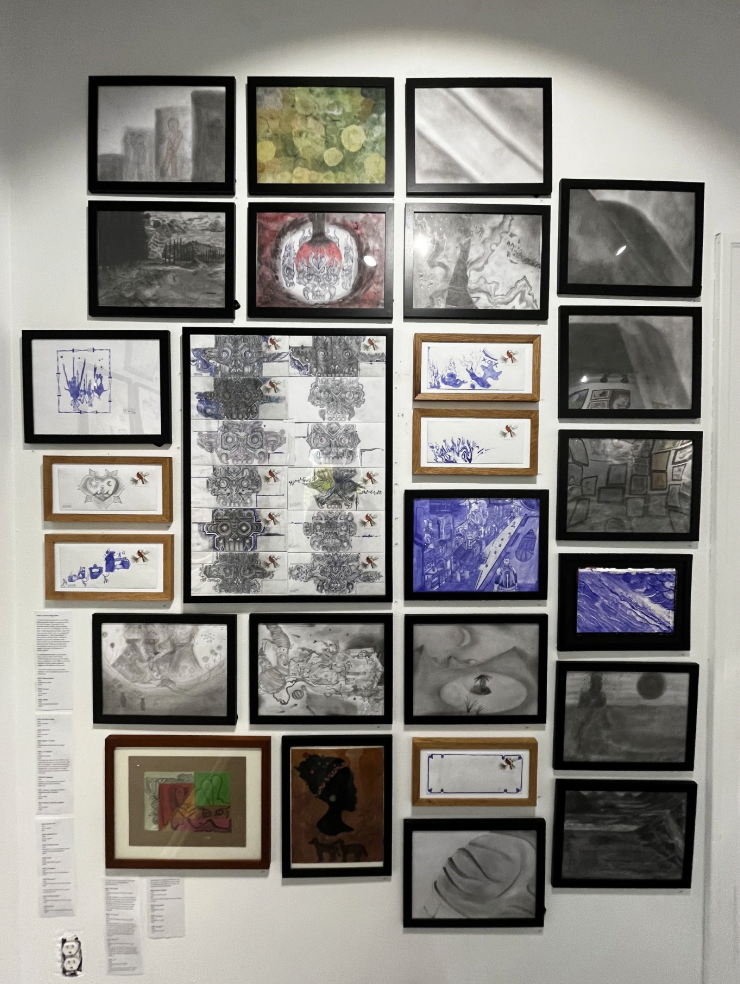

Unchain Whatcom works to make the creativity inside the jail visible to the public. In the cold concrete basement beneath the old auto shop on Flora Street, they hosted Unchained: Art From Inside Whatcom County Jail at Make.Shift Art Space. Envelope art, hand-drawn portraits, and pieces colored with coffee grounds and powdered pencil scrapings were all sold on a sliding scale. Every dollar went directly into the artist’s commissary account.

A wall of drawings, sketches, and mixed-media pieces created by people incarcerated in the Whatcom County Jail, displayed as part of “Unchained: Art From Inside” at Make.Shift Art Space.

By fall 2024, the collective was pressing on another fault line: visitation. The jail kept it suspended for nearly three years, well after Washington lifted its COVID restrictions, substituting in-person visits with glitchy, pay-by-the-minute video kiosks. Parents watched toddlers freeze and pixelate; partners couldn’t hold hands; sons couldn’t see their mothers.

Unchain Whatcom gathered testimony from pen pals and turned those letters into public comment, reading them aloud at county meetings where some officials visibly shifted in their seats.

The campaign escalated with community emails, petitions and organizers confronting Sheriff Donnell Tanksley during a public event. Two weeks later, Tanksley announced that in-person visitation would resume on Dec. 7, 2024. His statement made no mention of the organizing that spurred the change.

For Unchain Whatcom, the timing was “not coincidental.” The county always had the power to restore visitation; it simply waited until the public forced its hand.

Abolition as Art

What Unchain Whatcom is building isn’t a counterproposal or even a policy platform — it’s a different kind of relationship, one rooted in the belief that abolition, like art, begins with imagining what doesn’t yet exist.

County officials may call this unrealistic. The letters say otherwise.

They don’t mend leaking ceilings or ease overcrowding. They won’t stop construction crews from breaking ground. Still, each envelope disrupts distance, insisting on connection where the system insists on separation.

Each envelope reminds Lundstrom that someone inside is holding a pen, waiting for him to write back.